It has been more than 15 months since I returned from a pivotal, seminal and transmogrifying week in Alsace. The thoughts transposed to words continue to flow freely and with crystalline clarity. This may be the curtain call on that trip. Or not.

Type in the words “Alsace” and “philosophy” into a Google search page and the results will tell a Grand Cru story. The Alsace home page launches from terroir. It has to. Every winery, trade, marketing or governing organization’s website is ingrained to emphasize the rubric, to explain the true essence of Alsace wine. The local philosophy, indicating the cerebral and the spiritual component for producing exceptional wine, is both necessary and fundamental. There is nothing remotely parenthetical about the notion of terroir, not in Alsace.

Related – In a Grand Cru State of mind

As wine geeks we are constantly seeking it out and sometimes we imagine it, chat it up when it’s not really there. After we are immersed in Alsace, we cannot deny its existence. Terroir, defined as “the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography and climate.” Or, goûts de terroir, as in “taste of the earth.” Wherever wine is made around the world, soil is always as important, if not more important than any facet of the winemaking oeuvre. In Alsace, it is religion. I suss it, you suss it and in Alsace, they might say, “we all suss terroir.”

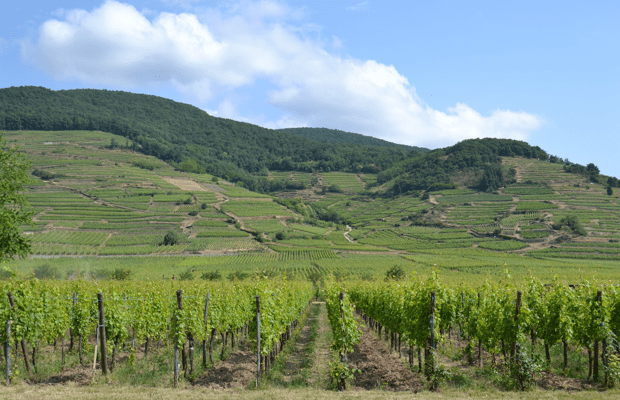

Alsace presents as a long strip of stupidly beautiful, verdant vistas, wedged between the faults and valleys forged with the Vosges Mountains on its west side and the Germany buffering Rhine River to the east. To consider its location as a province of France, drive 500 kilometres east of Paris and draw a line south from Strasbourg, to Colmar and to Basel. Wars have seen to make sure the region can never be too comfortable with its identity, causing an ever-annoying oscillation in governance.

Alsatians are the possessed refugees of Europe, tossed around like orphaned children from one foster family to another. That they can be so comfortable in their own skin is to accept their conceit as a French paradox, through ignoring its Franco-Germanic past, its passage back and forth between hands and its current state as a region governed by France. The confluence of cultures and of shared borders (and airports) would think to cause a crisis of identity. The names of towns and villages may act out a who’s who or what’s what of French sobriquet and German spitzname. None of that matters. The people, the places, the food and the wine are purely and unequivocally in ownership of their own vernacular, dialect and culture: Alsatian.

Phillipe Blanck in the Schlossberg

Photo (c): Cassidy Havens, http://teuwen.com/

Related – A Blanck slate in Alsace

When a winemaker wants to lay an insult upon you he will say something like “oh, that’s so Anglo-Saxon.” Ouch. He will mean it, for sure, but he will also grace you with a wink and a smile. He likes you and he respects your choice to come from far away to learn something of his wines. And you like him. The winemaker will also complement you when your palate aligns with his, when your thoughts intuit something about his acuity and his groove. His flattery will be genuine. The winemaker will pour old vintages and without a hem or a haw. She will share generously, not because she wants to sell more, but because she wants better people to drink her wine.

To ascertain a grip on the Alsace codex it must begin in the vineyard. The steep slopes, zig-zagging ridges and fertile valleys are composed of highly intricate, alternating and complex geological compositions. The landscape switches repeatedly from clay to marl, from calcaire (limestone) to schist, from volcanic to granitic rock. Each vineyard and even more parochial, each plot contributes to define the wine that will be made from that specific micro-parcel. The wine grower and winemaker’s job is to treat the soil with utmost respect. To plow the land, to add organic material, to refuse the use of fertilizers and to spray with solutions composed of non-chemical material.

Organic and biodynamic viticulture is widespread across the globe but Alsace is a leader in the practices, particularly in the latter’s holistic, asomatous way. Though more than 900 producers make wines, including many who do not partake in a bio-supernal and subterraneal kinship with the vines and the earth, the ones who do are fanatical about their winegrowing ways. Alsatian winemakers bond with their fruit, by employing the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner’s teachings as a predicate from which to apply spiritual connections to the physical act of tending vines.

Related – It was Josmeyer’s imagination

The belief is that great wine can only be made from healthy, natural and disease resistant plants. Steiner’s studies on chemical fertilizers looked into the effect on plants growing near bombs in the earth. The growth was observed to be abnormal and unhealthy. Christophe Ehrhart of Domaine Josmeyer compared this to humans, who eat too much salt and thus need to drink too much. I tasted more than 150 naturally made wines from biodynamically farmed soils. The proof of quality and complexity is in the glass.

The winemaker of Alsace shows a respect for the earth that might be seen as a verduous variation on the teachings of theologian, philosopher, physician, medical missionary and humanitarian Albert Schweitzer. The Alsatian-born Schweitzer gave to the world his theory on the “reverence for life,” a term he used for a universal concept of ethics. “He believed that such an ethic would reconcile the drives of altruism and egoism by requiring a respect for the lives of all other beings and by demanding the highest development of the individual’s resources.” The biodynamic approach, through its human to vegetable relationship, echoes the concept. Careful care not to disrupt the balance of nature allows the vines to develop the strength to survive and to flourish in less than optimum climatic conditions, especially during times of drought. The quality of grapes and in turn, the complexity of wine, is the result.

The focus on soil and terroir is ultimately disseminated into the idea of tasting minerality in wine, a most contentious aspect of the wine tasting and writing debate. Nary an expert will admit that the impart of trace minerals can be ascertained from a wine’s aroma and most believe that it can be found in taste. An American geologist debunked the mineral to taste theory at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America held in Portland Oregon. “The idea is romantic and highly useful commercially, but it is scientifically untenable,” wrote Alex Maltman, a professor at the Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University. Maltman’s claim is simple. Vines absorb minerals from the earth but the amount is far too small for human detection.

Christophe Ehrhart of Domaine Josmeyer in Wintzenheim agrees to disagree. Ehrhart concedes that the quantitative number is small (only three to five percent) for a vine to derive its personality, divined though the earth’s brine. The remainder is a consequence of photosynthesis. Ever the spiritual and natural advocate, Christophe borrows from the writings of David Lefebvre. The journalist and wine consultant’s The minerality from David Lefebvre tells the story of why natural wines without sulfur express minerality. Lefebvre makes clear the argument that naturally-farmed (biodynamic and/or, but necessarily organic) vines are qualitatively richer in (salt minerals) than those raised with chemicals. “All fermentation, from milk to cheese, from grape to wine, is accompanied by the appearance of the component saline, one could say mineral, in the taste of the fermented product.” Chemicals and fertilizers inhibit growth and vigor, ostensibly wiping out an already minuscule number. If food is available at the surface, vine roots will feed right there. They will then lose their ability to create the beneficial bacteria necessary to metabolize deep earth enzymatic material. They essentially abandon their will to fight for nutrition deep within the fissures of the rock. Lefebvre’s conclusion? “All biocides and other products that block mineralization, such as SO2, inhibit the expression mineral.”

At the end of the day Lefebvre is a wine taster and not a scientist and the argument must be considered within the realm of the natural world. “The taste of stone exists in Alsace, Burgundy, the Loire (all France) when the winegrower uses organic farming and indigenous, winemaking yeasts.” American made wine rarely does this, though change is occurring. Ontario winemakers are different. Taste the wines of Tawse or Southbrook and note the difference. Or, taste the difference a vegetable, like a tomato, or a piece of fruit, like a peach tastes when picked straight from the garden, or orchard, as opposed to the conventional piles of the supermarket. There can be no argument there.

Wihr au Val Photo (c): Cassidy Havens, http://teuwen.com/

A week tasting through nearly 300 wines in Alsace may sound exhausting when in fact it is an experience that had me constantly, “as the expression goes, gespannt wie ein Flitzebogens,” or as it is loosely employed from the German in the Grand Budapest Hotel, “that is, on the edge of my seat.” I watched Wes Anderson’s film on the Air France flight over from Toronto to Paris and enjoyed it so much that I watched it again on my return. That kind of spiritual, dry European humour is not unlike that of the fraternity of Alsatian winemakers and how they discuss their wines. From Olivier Zind-Humbrecht to Pierre Blanck, to MauriceBarthelmé and to Jean-Pierre Frick there is an Edward Norton to Bill Murray, Tom Wilkinson to Harvey Keitel, Adrien Brody to Ray Fiennes affinity. Or perhaps it’s just me.

Alsace is distinguished by a very specific set of vinous attributes. No other area in France is as dry and only Champagne is further north in latitude. The aridity of the summer months, followed by the humidity of the fall fosters the development of a beneficial fungus called Botrytis cinerea, the fungus better known as noble rot, which concentrates the sugars and preserves acidity. Pierre Gassmann of Rolly Gassman says all of his wines are noble rot wines, but he calls them Riesling.

The uninitiated into the wines of Alsace think it is one big pool of sickly sweet and cloying white wine. If perhaps this were, at least to some extent, once true, it is no longer. The progressive and philosophically attentive producer picks grapes (especially the particularly susceptible Pinot Gris) before the onset of botrytis. If a dry, mineral-driven style is the goal, picking must be complete before what Phillippe Zinck refers to as D-Day. Pinot Gris goes over the edge in an instant, even more so because of the advancing maturation due to the warm temperatures induced by Global Warming.

The global wine community’s ignorance to the multeity of Alsace wines, “as mutually producing and explaining each other…resulting in shapeliness,” needs addressing and so steps in the valedictorian, Christophe Ehrhart. The Josmeyer viniculturalist devised a system, a sugar scale to grace a bottle’s back label. Whites are coded from one to five, one being Sec (Dry) and five Doux (Sweet). The codification is not as simple as just incorporating residual sugar levels. Total acidity is taken into consideration against the sugar level, like a Football team’s plus-minus statistic. In Alsace the relationship between sugar, acidity and PH is unlike any other white wine region. Late Harvest (Vendanges Tardives, or Spätlese in German) is Late Harvest but Vin desprit sec or demi-sec in Alsace should not generally be correlated to similar distinctions in Champagne or the Loire. In Alsace, wines with vigorous levels of acidity and even more importantly PH bedeck of tannin and structure. Perceived sweetness is mitigated and many whites, though quantified with residual sugar numbering in the teens, or more, can seem totally dry.

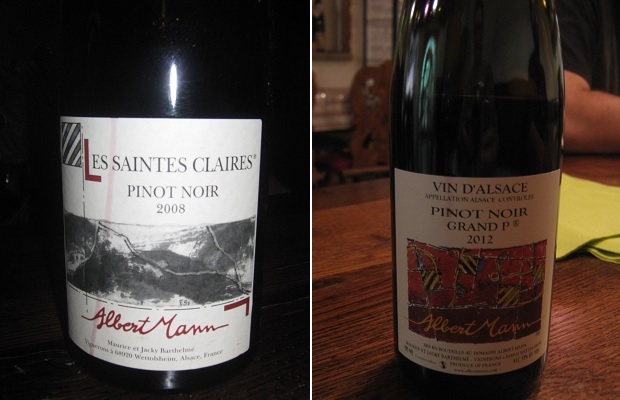

Returning to the idea of increasingly warmer seasonal temperatures, the red wines of Alsace have improved by leaps and bounds. “We could not have made Pinot Noir of this quality 20 years ago,” admits Maurice Barthelmé. Oh, the humanity and the irony of it all.

The Vineyards of Domaine Albert Mann

photo (c) https://www.facebook.com/albertmannwines

Related – Giving Grand Cru Pinot Noir d’Alsace its due

This sort of quirky response to nature and science is typical of the artisan winemaker. There is more humour, lightness of being and constater than anywhere else on this winemaking planet. There just seems to be a collective and pragmatic voice. Maurice makes a 10,000 case Riesling called Cuvee Albert, “because I have to make a wine for the market.” Yet Maurice is also a dreamer and a geologist. To him, “Pinot Noir, like Riesling, is a mineralogist.”

Domaine Albert Mann’s Jacky Barthelmé: “Before Jesus Christ was born we have had vines here in the Schlossberg. So it is a very old story.” The Alsace vigneron is only human and works in a vinous void of certitude. They do not fuck with their land or attempt to direct its course. The young Arnaud Baur of Domaine Charles Baur insists that you “don’t cheat with your terroir or it will catch up with you. You will be exposed. You can make a mistake but you will still lose the game.” What an even more wonderful world it would be if he only understood the complexity in his multiple entendre.

Philippe Blanck is a philosopher, a dreamer, an existentialist and a lover. He is Descartes, the aforementioned Bill Murray and Bob Dylan rolled into one, a man not of selection but of election. He is both prolific and also one who buys the whole record catalogue, not just the hits. He opens old vintages freely and without hesitation. When asked how often does he have the opportunity to open wines like these he answers simply, “when people come.”

Then there is the far-out Jean-Pierre Frick, the man who let a 2006 Auxerrois ferment for five years before bottling it in 2011. “After one year I check the wine and he is not ready. I see him after two years and he says I am not ready. So I wait. After five years he says, I am finished. So I put him in the bottle.” On his Riesling 2012 he says, “This is a wine for mouse feeding.” Upon cracking open his remarkable, natural winemaking at its peak 2010 Sylvaner he chuckles like M. Gustave and smirks, “he is a funny wine.”

Few wine regions tell their story through geology as succinctly and in as much variegated detail as Alsace. The exploration of its Grand (and other vital) Cru (for the purposes of this trip) was through soils (or not) variegated of clay, sandy clay, marl, granite, volcanic rock, limestone and sandstone. To complicate things further, a Cru can be composed of more than one type of terra firma and still others have more than one arrangement within the particular plot. All very complicated and yet so simple at the same time. The Crus tasted came from the following:

Schlossberg Grand Cru, (c) Cassidy Havens, http://teuwen.com/

- Granitique/Granite (Brand, Herrenreben, Kaefferkopf, Langenberg, Linsenberg, Schlossberg, Sommerberg)

Domaine Schoenheitz Linsenberg Riesling 1990, Ac Alsace, France (Winery, 196618, WineAlign)

During a picnic, on a plateau up on the Linsenberg lieu-dit set above the Wihr-au-Val, this 24 year-old bottle acts as a kind of Alsatian Trou Normand. A pause between courses, which involves alcohol and you need to ask for its proof of age. Culled from deep dug vines out of stony and shallow granite soil. Soil rich in micas with a fractured basement. From a dream vintage with marvellous semi-low yields and a student of south-facing, self-effacing steep steppes. A sun worshipper prodigy of winemaker Henri Schoenheitz, a child of terroir du solaire. Rich and arid in simultaneous fashion (the RS is only 8-10 g/L), the years have yet to add mileage to its face and its internal clock. It may ride another 15, or 20. Drink 2015-2030. Tasted June 2015 @VinsSchoenheitz

Domaine Albert Boxler Pinot Blanc Reserve 2013, Ac Alsace, France (SAQ $27.70 11903328, WineAlign)

From fruit drawn off the granitic Grand Cru of the Brand but not labeled as such. Laser focus (what Jean Boxler wine is not) and texture. Possessive of the unmistakable Brand tang, like mineral rich Burgundy. The minerality ann the acidity from the granite are exceptional in a wine known as “Pinot Blanc Reserve.” As good a developing PB are you are ever likely to taste. Drink 2015-2019. Tasted June 2014

Domaine Albert Boxler Riesling Old Vines Sommerberg Grand Cru 2013, Ac Alsace, France (SAQ, 11698521, WineAlign)

A direct expression of winemaker (since 1996) Jean Boxler and his 150 year-old casks. This is Riesling suspended in the realm of dry extract, texture and a precision of finesse rarely paralleled in Alsace. It reads the truth of facteur for Sommerberg, its face, slope and pitch. Exceeds the clarity of the younger parcel in its contiguous continuance of learning, of pure, linear, laser styling. There is more maturity here and the must had to have been exceptional. “The juice must be balanced when it goes into the vats or the wine will not be balanced,” insists Jean Boxler. And he would be correct. Drink 2016-2025. Tasted June 2014

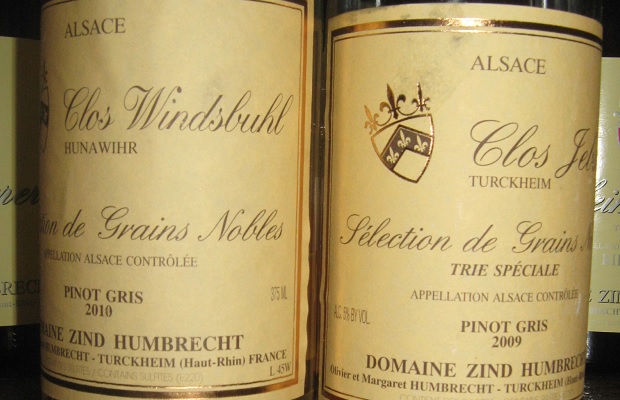

Domaine Albert Boxler Tokay-Pinot Gris Sommerberg Grand Cru 1996, Ac Alsace, France (Alsace)

From volcanic and granitic soils together combining for and equating to structure. A matter concerning “purity of what you can do from a great ground,” notes Master Sommelier Romain Iltis. Perception is stronger than reality because despite the sugar, the acidity reign to lead this to be imagined and reasoned as a dry wine. Ripe, fresh, smoky, with crushed hazelnut and seamless structure. Stays focused and intense in mouthfeel. Takes the wine down a long, long road. Quite remarkable. No longer labeled “Takay” after the 2007 vintage. Drink 2015-2026. Tasted June 2014

- Calcaire/Limestone (Engelgarten, Furstentum, Goldert, Rosenbourg, Rotenberg, Schoffweg)

Domaine Albert Mann Pinot Gris Grand Cru Furstentum 2008, Alsace, France (Winery)

The Marl accentuated Hengst and its muscular heft receives more Barthelmé limelight but the always understated Furstentum Grand Cru is a special expression of the variety. As refined as Pinot Gris can be, with a healthy level of residual sugar, “like me” smiles Marie-Thérèse Barthelmé. The sugar polls late to the party while the acidity swells in pools, but the finish is forever. “Pinot Gris is a fabulous grape but we serve it too young,” says Maurice. “It needs time to develop its sugars.” Truffle, mushroom, underbrush and stone fruit would match well to sweet and sour cuisine. Flinty mineral arrives and despite the residual obstacle, is able to hop the sweet fencing. The potential here is boundless. Drink 2018-2026. Tasted June 2014 @albertmannwines

Domaine Paul Zinck Gewürztraminer Grand Cru Goldert 2010, Alsace, France (Agent)

From the village of Gueberschwihr and from soil composed of sandstone, chalk and clay. The vines average 50 years in age and the wine saw a maturation on the lees for 11 months. Philippe Zinck notes that “the terroir is stronger than the variety.” If any grape would stand to contradict that statement it would be Gewürztraminer but the ’10 Goldert begs to differ. Its herbal, arid Mediterranean quality can only be Goldert talking. Though it measures 20 g/L of RS it tastes almost perfectly dry. It reeks of lemongrass, fresh, split and emanating distilled florals. This is classic and quintessential stuff. Drink 2015-2025. Tasted June 2014 @domainezinck @LiffordON

Domaine Zind-Humbrecht Gewürztraminer Vendanges Tardives Goldert Grand Cru 1985

Tasted from magnum at Les Millésimes Alsace, a wine described by Caroline Furstoss as “unusual for late harvest,” because the terroir is simply stronger than the variety. Another economically non-viable low yield LH, “from a vintage more on the reductive than the oxidative side.” Even at 30 years it requires aeration and time to open up. Travels from spicy to smoky with that air. There is a density in bitterness, an attrition miles away from resolve and a promise for rebate, if further patience is granted. The spices inherent are ground, exhumed and combine with the base elements to rise atomically. A spatially magnificent wine of sugars not yet clarified and an acquired taste not quite elucidated. A taste of an ancient kind. Drink 2015-2035. Tasted June 2014

- Marno-Calcaire/Marl-Limestone (Altenberg de Bergheim, Clos Hauserer, Eichberg, Hengst, Kappelweg de Rorschwihr, Mambourg, Mandelberg, Osterberg, Pfersigberg, Sonnenglanz, Steingrubler)

Marcel Deiss Schoffweg “Le Chemins Des Brebis” 2010, Bergheim, Alsace, France (Agent, $60.95, WineAlign)

A pulsating and metallic, mineral streak turns the screws directly through this spirited Bergheim. From Schoffweg, one of nine Deiss Premier Crus planted to Riesling and Pinots. A pour at Domaine Stentz Buecher from fellow winemaker Carolyn Sipp simulates a trip, to stand upon a scree of calcaire, the earth below a mirror, reflecting above a multitude of stars. “He’s a character,” smiles Sipp, “and perhaps even he does not know the actual blend.” The amalgamate is surely Riesling dominant, at least in this impetuous ’10, a savant of fleshy breadth and caracoling acidity. The Schoffweg does not sprint in any direction. It is purposed and precise, geometric, linear and prolonging of the Deiss magic. This is a different piece of cake, an ulterior approach to assemblage, “a bigger better slice” of Alsace. It should not be missed. Tasted June 2014 @LeSommelierWine

Marcel Deiss Mambourg Grand Cru 2011, Bergheim, Alsace, France (Agent, $114.95, WineAlign)

In a select portfolio tasting that includes a trio of highly mineral yet approachable 2010’s (Rotenberg, Schoffberg and Schoenenbourg), the ’11 Mambourg stands out for its barbarous youth. It seems purposely reductive and strobes like a hyper-intensified beacon. Rigid, reserved and unforgiving, the Mambourg is also dense and viscous. Acts of propellant and wet concrete circulate in the tank, compress and further the dangerous liaison. This is a brooding Deiss, so different than the jurassic citrus from Rotenberg, the terroir monster in Schoffberg and the weight of Schoenenbourg. In a field of supervised beauty, the Mambourg may seem like punishment but there can be no denying the attraction. Five years will alter the laws of its physics and soften its biology. The difficult childhood will be forgotten. Drink 2019-2026. Tasted June 2014 @LeSommelierWine

Marcel Deiss Langenberg “La Longue Colline” 2011, Bergheim, Alsace, France (Agent, $48.95, WineAlign)

Rogue Alsace, classic Deiss five varietal field blend specific to one hangout. The steep, terraced, granite Langenberg, terroir from Saint Hippolyte. Deiss coaxes, expects and demands precocious behaviour from four supporting varieties to lift and place the Riesling, with the intent being a result in “salty symphony.” This is approachable, something 2011 could not have been easy to accomplish. The accents are spice, sapidity and acidity, from the granite, for the people. Isn’t this what a mischievous brew should be about? Drink 2015-2022. Tasted June 2014 @LeSommelierWine

Léon Beyer Riesling Cuvée Des Comtes D’Eguisheim 1985, Alsace, France (316174, $50.00, WineAlign)

I wonder is any Alsace Riesling sublimates history, religion and occupation more than Cuvée Des Comtes D’eguisheim. It breathes the past; of popes, Augustinians of Marbach, Benedictines of Ebersmunster, Cistercians of Paris and Dominicans of Colmar. From the limestone-clay for the most part of the Grand Cru Pfersigberg and only produced in exceptional vintages. In 1985 low yields, same for botrytis and then 29 years of low and slow maturation. In 2014, is the herbal, aromatic, limestone salinity a case of vineyards, grape or evolution? All of the above but time is in charge. It has evolved exactly as it should, as its makers would have wished for. It is ready to drink. The defined minerality, with fresh lemon and a struck flint spark has rounded out, without the need for sugar. Drink 2015-2017. Tasted June 2014 @TandemSelection

Charles Baur Riesling Grand Cru Eichberg 2009, Ac Alsace, France (Winery)

Arnaud Baur understands his place and his family’s position in the Alsace continuum. “You can make a mistake and you can still lose the game.” His use of entendre is subconsciously brilliant. In 2009 the warmth went on seemingly forever and so Baur did not even bother trying to make a dry Riesling. “We really respect the vintage,” says Arnaud. Meanwhile at 18 g/L RS and 7.0 g/L TA the balance is struck. Many grapes were dried by the sun, ripeness was rampant, flavours travelled to tropical and acidity went lemon linear. The 14.2 per cent alcohol concludes these activities. Matched with foie gras, the vintage is marinated and married. There is certainly some crème fraîche on the nose and the wine plays a beautiful, funky beat. As much fun and quivering vibration as you will find in Alsace Marno-Calcaire. Drink 2015-2024. Tasted June 2014

Charles Baur Gewürztraminer Grand Cru Pfersigberg 2007, Ac Alsace, France (Winery)

A good vintage for Riesling and considering the heat, an even better one for Gewürztraminer. The vineyard offers 50-70cm of clay atop Jurassic yellow limestone where roots can penetrate the rock. They suck the life into this enzymatic white. This, of digestibility, “a wine you don’t want to drink two glasses of, but three.” Delicious, clean, precise Gewürz that Mr. Baur recommends you “drink moderately, but drink a lot.” Arnaud is very proud of this ’07, for good reason. Two actually. Balance and length. Drink 2017-2027. Tasted June 2014

Domaine Albert Mann Pinot Gris Grand Cru Hengst 2013, Alsace, France (SAQ $41.50 11343711, WineAlign)

Tasted not long after bottling, the yet labeled ’13 is drawn from a vintage with a touch of botrytis. “We don’t sell too much of this,” admits Maurice Barthelmé. Along with the sweet entry there are herbs and some spice, in layers upon layers. Almost savoury, this interest lies in the interchange between sweet and savour, with stone fruit (peach and apricot) elevated by a feeling of fumée. A playful, postmodernist style of short fiction. Drink 2017-2024. Tasted June 2015 @albertmannwines @Smallwinemakers

Domaine Albert Mann Pinot Gris Grand Cru Hengst 2008, Alsace, France (SAQ $41.50 11343711, WineAlign)

In 2008 the brothers Barthelmé used the Hengst’s strength and the vintage to fashion a remarkable Pinot Gris. It is blessed of antiquity, like concrete to bitters, with power, tension and a posit tub between fruit and sugar. At 34 g/L RS and 7.6 g/L TA there is enough centrifuge to whirl, whorl and pop, culminating in a healthy alcohol at 14 per cent. Quite the reductive Pinot Gris, to this day, with a sweetness that is manifested in mineral flavours, glazed in crushed rocks. “It smells like mushroom you threw into a dead fire,” notes Fred Fortin. This is the bomb. Needs four more years to develop another gear. Drink 2018-2033. Tasted June 2015 @albertmannwines @Smallwinemakers

Domaine Albert Mann Gewürztraminer Grand Cru Steingrubler 2008, Alsace, France (Winery)

From marly-limestone-sandstone, “a fa-bulous terroir,” says Maurice with a smile. The “stone carrier wagon” is mostly calcaire, especially in the middle slope. This has a roundness, an approachability. It really is clean, clean, Gewürztraminer. It’s erotic, gorgeous, certainly not slutty or pornographic. The colder limestone preserves the freshness, with a need for magnesium, to cool the factor further and to develop the terpenes. Gelid and stone cold cool wine. Drink 2018-2035. Tasted June 2015 @albertmannwines @Smallwinemakers

Bott Geyl Riesling Grand Cru Mandelberg 2010, Alsace, France (Agent)

The Mandelberg receives the early morning sun and so this Grand Cru is an early ripener and the first of the Bott-Geyls to be picked. The added warmth of 2010 introduced noble rot into a vineyard that often avoids it so the residual sugar here is elevated to an off-dry (even for Alsace) number of 30 g/L. The rush to pick in this case preserved the natural acidity, allowing the flint to speak. Additional notes of cream cheese and formidable dry extract have helped to balance the sweetness. Truly exceptional Riesling from Christophe Bott-Geyl. Drink 2015-2025. Tasted June 2014 @bott_geyl @DanielBeiles

- Calcaro-gréseux/Limestone-Sandstone (Bergweingarten, Zinkoepfle)

Pierre Frick Sylvaner Bergweingarten 2010, Alsace, France (Winery)

The vines of southeast exposure are in the 35 year-old range for this Vin moelleux, “young vines” says Jean-Pierre Frick. “I am a defender of Sylvaner.” This ’10 is freshly opened, as opposed to the ’09 poured after sitting open a week. That ’09’s healthy amount of noble rot is not repeated in this ’10, what Frick refers to as “a funny wine.” A two year fermentation and a potential for 17 per cent alcohol (it’s actually in the 14-15 range), a touch of spritz and no sulphur means it goes it alone, natural, naked, innocent. It’s a passionate, iconoclastic Sylvaner, distilled and concentrated from and in lemon/lime. It may carry 53 g/L of sugar but it also totes huge acidity. Enamel stripping acidity. Full of energy, that is its calling, its niche, its category. The honey is pure and despite the level of alcohol it’s as though it has never actually fermented. Natural winemaking at the apex, not out of intent but from a base and simply purposed necessity. Drink 2015-2025. Tasted June 2014 @LeCavisteTO

- Sablo-Argileux/Sandy-Clay (Schlossberg)

Domaine Albert Mann Riesling Schlossberg Grand Cru 2008, Alsace, France (SAQ 11967751 $48.25, WineAlign)

What a fantastic expression of the Schlossberg, like a cold granite countertop. A Riesling that tells you what is essentiality in granite from what you thought might be the sensation of petrol. Full output of crushed stone, flint and magnesium, but never petrol. Now just beginning to enter its gold stage, just beginning to warm up, in energy, in the sound of the alarm clock. “You can almost see the rock breaking and the smoke rising out,” remarks Eleven Madison Park’s Jonathan Ross. A definitive sketch with a 12 g/L sugar quotient lost in the structure of its terroir. A Schlossberg a day keeps the doctor away. Drink 2015-2025. Tasted June 2014

Related – Arch classic Alsace at Domaine Weinbach

Domaine Weinbach, (c) Cassidy Havens, http://teuwen.com/

- Argilo-calcaro-gréseux/Clay-Limestone-Sandstone (Goldert, Vorbourg)

Pierre Frick Auxerrois Carrière 2006 (Embouteille en 2011), Alsace, France (Winery)

“He has fermented five years,” says Jean-Pierre Frick, stone faced, matter of factly. “That’s how long he took.” Here, one of the most impossible, idiosyncratic and unusual wines made anywhere in the world. On on hand it’s a strange but beautiful experiment. On another there can be no logical explanation as to why one would bother. The third makes perfect sense; allowing a wine to ferment at its own speed, advocate for itself and become what it inherently wanted to be. Auxerrois with a little bit of sweetness (16 g/L RS) and a kindred spirit to the Jura (and with a potential of 15 per cent alcohol). This is drawn from the lieu-dit terroir Krottenfues, of marl-sandstone soils in the hills above the Grand Cru Vorbourg. Tasting this wine is like slumbering through a murky and demurred dream. Drink 2015-2021. Tasted September 2015

- Argilo-calcaire/Clay-Limestone (Eichberg, Engelberg, Kanzlernerg, Pflaenzerreben de Rorschwihr, Steinert)

Paul & Phillipe Zinck Pinot Blanc Terroir 2011, Alsace, France (BCLDB 414557 $15.79, WineAlign)

From 35 year-old vines on Eguisheim’s argilo-calcaire slopes with straight out acidity, trailed by earth-driven fruit. Less floral than some and pushed by the mineral. A difficult vintage that saw a full heat spike to cause a mid-palate grape unction. Pinot Blanc with a late vintage complex because of that sun on the mid slope. Drink 2015-2017. Tasted June 2014 @domainezinck @LiffordON

Paul & Phillipe Zinck Pinot Gris Terroir 2012, Alsace, France (Agent, $22.99, WineAlign)

From chalk and clay soils surrounding the Eichberg Grand Cru, this is a decidedly terroir-driven style and far from overripe. In fact, Philippe Zinck is adamant about picking time, especially with Pinot Gris. “The most tricky grape to harvest in Alsace,” he tells me. So hard to get serious structure and many growers are duped by high brix. Philippe tells of the 24-hour varietal picking window, the “D-Day” grape. Zinck’s ’12 is pure, balanced and bound by its earthy character. Drink 2015-2017. Tasted June 2014 @domainezinck @LiffordON

Pierre Frick Muscat Grand Cru Steinert Sélection de Grains Nobles 2010, Alsace, France (Winery)

“I like acidity, whoo-ahh,” says Pierre Frick, dry as Monsieur Ivan. The sugar on top of acidity here, it’s exciting. This one is a gift from nature, for culture. So interesting, a dream, a story. This has a citrus sweetness, telling a story never before experienced. There’s a depth of reduced apricot syrup, pure, natural, holy. “Tell no one. They’ll explain everything.” Drink 2015-2040. Tasted June 2014

- Volcano-gréseux/Volcanic sandstone (Kitterlé, Muenchberg)

Pierre Frick Pinot Gris Sélection de Grains Nobles 1992, Alsace, France (Winery)

From Argilo-Calcaire vineyards flanking the Rot Murlé, at a time when a minor amount of sulphuring was employed (1999 was their first sulphur-free vintage). Was Demeter certified, in 1992! This is all about intensity and acidity. An incredibly natural dessert wine, upwards of 150 g/L RS but balanced by nearly 10 g/L TA. The power is relentless, the finish on the road to never-ending. Drink 2015-2022. Tasted September 2015

Domaine Ostertag Tokay Pinot Gris Grand Cru Muenchberg 1996, Alsace, France (Agent, $65, WineAlign)

From clay and limestone, fully aged in barrel, taking, sending and stratifying in and away from its own and everyone else’s comfort zone. Only the best barrels would do and yet the quality of the wood thought aside, this is Ostertag’s unique and fully autocratic take on Tokay-PG. Stands out with a structure wholly singular for the overall prefecture, with a twenty year note of white truffle, handled and enhanced by the wood maturation. Yellow fruits persist as if they were picked just yesterday but the glass is commandeered by the complex funk. It’s nearly outrageous, bracing and yet the flavour urged on by the aromatics return to their youth. To citron, ginger and tropical unction. This is oscillating and magnificent. Drink 2015-2026. Tasted June 2014 @TheLivingVine

- Argilo-Granitique/Clay-Granite (Kaefferkopf, Sonnenberg)

Audrey et Christian Binner Grand Cru Kaefferkopf 2010, Alsace France (Winery)

A blend of Gewürztraminer (60 per cent), Riesling (30) and Muscat (10) that spent two years in foudres. Christian has no time for technicalities, specs and conventions. “I just make wine.” At 13.5 per cent alcohol and 20 g/L RS the expectation would be vitality and striking lines but it’s really quite oxidative, natural and nearly orange. “But it’s OK. It’s the life,” he adds. An acquired, unique and at times extraordinary taste, complex, demanding, like Frick but further down a certain line. “For me, to be a great Alsace wine, it must be easy to drink. You have to pout it in your body.” Drink 2015-2019. Tasted September 2015

Related – Walking an Alsace mile in their Riesling shoes

- Volcanique/Clay-Granite (Rangen)

Related – Colmar and the volcano: Domaine Schoffit

- Marno-Calcaire-gréseux/Marl- Limestone-Sandstone (Altenbourg, Kirchberg de Ribeauvillé)

- Volcano-sédiment/Volcanic Sediment (Rangen)

- Graves du quaternaire/Alluvial (Herrenweg de Turckheim)

Related – The cru chief of Alsace: Zind Humbrecht

Olivier Humbrecht and Godello

PHOTO: Cassidy Havens, http://teuwen.com/

- Roche Volcanique/Volcanic rocks (Rangen de Thann)

- Marno-gypseux/Marl-gypsum (Schoenenbourg)

You see, no wine is poured, tasted and deliberated over without the introduction of the soil (or lack thereof) from which it came. To confine any study to just the Grand Cru would do the entire region an injustice. Though the original 1975 appellative system set out to define the plots of highest quality and esteem, many wines not classified GC are fashioned from terroir comingling with, surrounding, located next or adjacent to a vineyard called Grand Cru. Serious consideration is being given by CIVA and the winemakers to establish a Premier Cru and Villages system. While this will certainly increase levels of definition and understanding for Alsace, it may also disregard some quality wines, not to mention further alienate some producers whose artisanal and progressive wines go against the norm. A further consequence may result in elevating some average wines currently labeled Grand Cru into undeserved stratospheres.

Related – Trimbach, rhythm and soul

The Grand Cru story is heavy but not everything. Rarely has there been witnessed (outside of Burgundy) the kind of symbiotic relationship between vineyard and village. Perfect examples are those like Schlossberg and Furstentum with Kintzheim, Sommerberg and Niedermorschwihr, Hengst and Wintzenheim, Brand and Turckheim or Steingrübler and Wettolsheim. Domaine Weinbach’s cellars sit across and just down the road from both Kitzheim and Kayserberg. Albert Boxler’s cellar is right in the fairy tale town of Niedermorschwihr, just like Albert Mann’s location in Wettlosheim.

It is time, finally and thankfully, for a return to the reason for such a rambling on. With respect to the “cerebral and the spiritual component for producing exceptional wine” being “necessary and fundamental,” examples tasted in June of 2014 indicate that the notion of terroir grows from nature and is nurtured by the vigneron. These 25 wines surmise and summarize, either by connecting the dotted lines of constellatory figuration or by Sudoku interconnectivity, the imaginable chronicle that is Alsace.

Good to go!